Written by:

Universities and other research institutions are increasingly interested in working with community and voluntary sector partners through research. Many are setting up dedicated programmes to encourage such research partnerships and academic researchers are often seeking communities in which they can ground their research activities.

The Glass-House is fortunate to have enjoyed a rare strategic partnership with The Open University’s Design Group for over a decade, which has seen us co-design and co-produce 17 action research projects working directly and collaboratively with communities around the UK, as well as various other initiatives. This enduring partnership is built on shared values and a commitment to community leadership and cross-sector collaboration in design and placemaking. It has also endured, both within and outside periods of dedicated funding, thanks to a strong sense of both mutual respect and friendship within our research team.

Whilst we have celebrated the successes of this partnership through a previous blog, Celebrating a Decade of Strategic Partnership with The Open University, we have not spoken publicly about some of the opportunities and challenges, in broad terms, of being a small charity working with a higher education institution through funded research. In the current socio-political and funding landscape, we thought it might be useful to share this to help third sector partners thinking about collaborating with higher education through funded research. We hope that it might also help academics be more mindful in how they approach and work with community and voluntary sector partners.

The Magic of Collaborative Research with Higher Education Partners

Let’s start with the aspects of these collaborations that we have really enjoyed and that have added considerable value to furthering our charitable objectives:

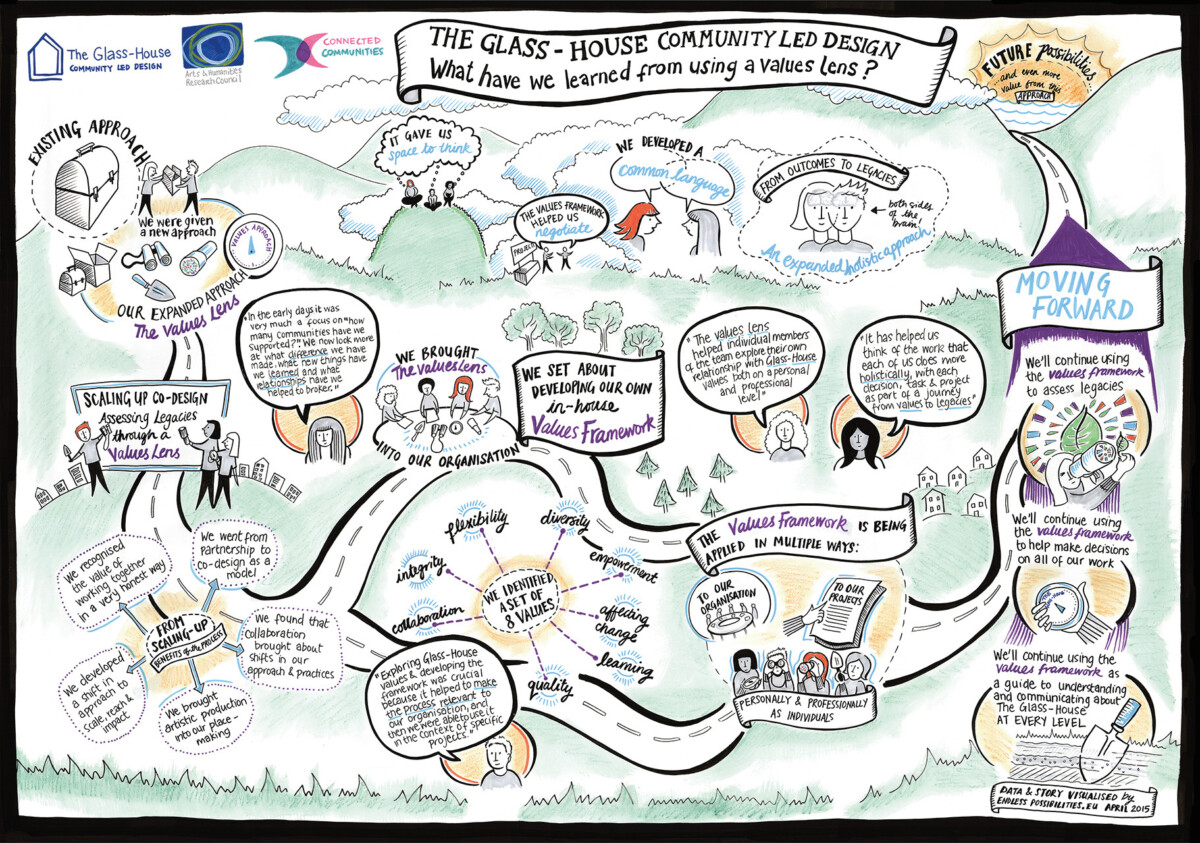

1. A safe space for experimentation

Many charities find themselves on a target-driven, deliverable treadmill. When designed well, collaborative action research can offer a space to slow down and simply try things, potentially changing direction responsively as you go. Within a research context, one is able to take risks and to encourage other partners across sectors to do so with you. We have had public and private sector partners tell us that working with us through research has allowed them to try things that simply wouldn’t be possible through traditional project funding or commissioning.

2. Operational budgets to innovate with communities

Research funding is designed to create spaces for innovation, prototyping and learning. Working with communities in an ethical and inclusive way through research can help inject resources directly into communities to do this. This is most effective when research is co-designed with community partners to build on and contribute to existing community infrastructures and activities and incorporates spaces for reflection and for capturing, evaluating and sharing impact and learning.

3. Space and resources to support reflection, learning and sharing

Evaluation and impact assessment are a key feature of well-designed research, and creating structured and funded time and space for this is something that has been of enormous value to us as an organisation and to the communities engaging with us through research. Working with higher education partners has also helped bring rigour to how we capture and share learning and build evidence.

At the same time, third sector partners can be absolutely crucial in ensuring that research connects with real life issues and can actually make a tangible difference to people and communities. The Glass-House has been able to help ensure that learning from our collaborative research projects is shared outside academia, and that it informs and includes the production of practical tools, methods and resources. We can also help ensure that what we produce is accessible to communities and that it can help inform policy and practice.

4. The value of embedding and furthering research outcomes in practice

Research and innovation does not fit neatly into project dates, and we have found that continuing to use, develop and learn from research projects through our work in practice, has been hugely important to our enduring research partnership. Those in between spaces allow us to apply our learning in new contexts, with different partners and communities. This extends the outcomes and impact of past research, creates new opportunities for innovation and informs new research projects.

It is important to capture this ongoing research, innovation and learning by practice and community-based partners, otherwise it risks being undervalued in the research community. Enduring partnerships can help ensure continuity and prevent this impact from slipping through the net.

The Challenges of Collaborative Research

However, research funding is not without its challenges, and community and voluntary sectors groups and organisations should be aware of these if they are looking to build research funding into their programming. The challenges below are generalisations from looking across the sector, but perhaps serve as useful notes of caution.

1. Research funding models

Research funding is designed primarily to support higher education and other officially recognised research institutions, and most of it must be led by them. It is rare for practice, community or voluntary sector partners to be officially recognised as co-investigators, and though named as partners, they often have to be officially contracted by the lead university as a consultant if they are allocated any funding for their time and contribution to the project.

While some academic researchers fight hard to recognise the contribution of their third sector partners with adequate recognition and funding, sadly many research projects rely heavily on community and voluntary sector partners and collaborators donating their time with minimal per diem rates, on a pro-bono basis, or simply having expenses covered. It is therefore essential to co-design research projects in a way that builds in adequate resources to make the investment viable and rewarding for community and voluntary sector partners.

2. Bid writing and application timescales

Preparing any funding application takes time. Truly co-designed research funding bids require a significant investment of time to ensure that the project can meaningfully add value to all those involved in the project and, at the same time, create novel research and learning. Whilst academic research institutions may have allocated and funded time in their budgets to develop these bids, third sector organisations must be willing and able to invest the time to do so. Many can struggle to do so.

It is also worth noting that the research funding application assessment process is long and unpredictable. With a standard grant application for UKRI taking between 6 months and a year to process, circumstances can change dramatically for community or voluntary sector organisations and groups between the application submission and funding outcome. These timescales can make it feel hard to invest time in these funding bids, when third sector organisations are facing short-term as well as medium-term fundraising objectives.

3. Current funding for projects, not partnerships

The vast majority of funding goes to funding fixed term projects, often for short periods of time with predetermined targets deliverables and outputs. While research funding does create more flexibility in terms of creating space for research and innovation, and for potential shifts in direction of travel, it is still predominantly project-based.

There is currently far too little investment in partnership working itself, in resourcing the time it takes for partners to work together to meaningfully co-design and co-resource projects that will be beneficial to all involved and that can be responsive to real-world challenges in practicable timescales.

This focus on project funding also makes it difficult for partnerships to endure, and for those spaces between projects to provide opportunities for continuity in research and development in shared fields of interest. Similarly, project-based funding makes it difficult to capture medium and long-term impact and the social capital that emerges over time from work delivered within the boundaries of a project. Instead it encourages a culture of delivering a project, wrapping it up and moving on to the next one.

Invest in Partnerships

The Glass-House / Open University strategic partnership is a strong advocate of investing in partnerships rather than just projects, whether they be cross-sector research collaborations or community networks to nurture organic opportunities for collaborative action.

Earlier this month, we shared findings and recommendations from our recent research project, Cross-pollination: Growing cross-sector design collaboration in placemaking in collaboration with The Open University and 13 local partners in England, Scotland and Wales. The project was funded through the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Place-Based Research Programme and saw us working with over 50 organisations and 450 individuals over a 16-month period.

Two of the key recommendations from our policy brief1 were:

- Direct funding towards cross-sector collaborations, partnerships and networks as well as projects.

- Invest in long-term community-academic research partnerships, by providing funding to non-academic organisations for their participation in bid development and ongoing work to embed research findings & outputs into practice and communities.

Whilst these have emerged very specifically from the Cross-pollination project, they are recommendations that are grounded in the experience of our enduring partnership with The Open University over more than a decade.

Cross-sector collaboration through research has so much potential. We encourage funders, higher education and funders to invest in truly co-designed and co-produced research and to partnerships, not just projects. There is a lot we can do if we all work more strategically together.

- You can read the full policy brief, Enabling integrative leadership and cross-sector design collaboration: insights from the Cross-pollination project here. This summarises our key findings, both around the outcomes of the cross-pollination approach and the conditions for integrative leadership, as well as our recommendations to policy makers, local authorities, practitioners and funders. ↩︎