Written by:

by Olivia Hanson

Olivia taught secondary school English and ran a street kitchen in Hackney until 2021, when she started an MA in Intercultural Conflict Management in Berlin. While there, her interest in housing and spatial justice continued to grow. She set up FlatWise, a housing advice programme for refugees and immigrants, and wrote extensively for her Masters about the impacts of gentrification and privatisation on urban populations. Undertaking months of qualitative research for her thesis, she focused on several ‘community-made’ places that are threatened by corporate and infrastructure projects, analysing their importance to their Berlin neighbourhood and beyond. With her thesis completed, she continues to be involved in housing activism and to run FlatWise workshops, while looking for a role in the NGO or public sector.

‘What begins as undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value.’ Yi-Fu Tuan

‘When humans invest meaning in a portion of space and then become attached to it in some way (naming is one such way) it becomes a place.’ Tim Cresswell

Dear Future Placemaker,

You have a brief incoming. It involves making a new place, perhaps by transforming an existing one or by building something completely new. Perhaps you’re working on behalf of a private developer, or for a local council, or with a community group. Whichever it is, before you start planning, ask yourself these questions first:

1 – Only very rarely these days is it possible to make a new place in a space where nothing at all exists, and to which no one is in some way attached. Before deciding that a new place is needed, take a look at what is already there. What purpose is it serving? Who uses it? Will they still feel welcome when it’s become a different place? Take inspiration from the French architects Lacaton and Vassal, whose motto is: ‘Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform and reuse!’ An example: asked to redesign a public square in Bordeaux, Lacaton and Vassal decided to see for themselves what was wrong with it… and found nothing wrong at all. They saw people playing pétanque, reading on benches and chatting with passersby. They refused the brief – no redesign required. Is your brief solving a problem? And if it is, is it the right problem to solve? Is it working with existing resources? Can it be adapted so that it does?

2 – Observe the place at different times of day or night. Talk to the people who use it. Better yet, go on a walk with them around the neighbourhood, listen to them speak about the places that are important to them. Try to see the place through their eyes. To you it might seem like a ‘nothing-special’ café, or off-licence, or park, but to them, it might be where the neighbourhood meets, where mutual support is offered and received, or where community memories are kept. It might be none of these things, and in dire need of change, but it is worth checking first. And if it is important to people – how can you incorporate it into your plans… or leave it alone?

3 – It is hard to overestimate the strength of the bonds that form between people and places. The cultural geographer, Dr. Karen Till, describes what she calls ‘root shock’: the trauma of being displaced or watching a place you love disappear. If your placemaking project necessitates either or both of these things, how will you manage this process? Do you need to create some guidelines for communication with the community? Does every member of your team know that empathy and dialogue are essential? Should you create space for discussion and exchange? Can you provide for an alternative to this place in your plans?

Right: an ‘anti-demolition’ action group organises tours through the city that are dedicated to buildings and areas pegged for demolition and redevelopment. They oppose demolition on environmental, financial and social grounds. Author’s own photo, April 2023.

4 – Consider the place you want to make not in terms of its economic value, but as an element of the surrounding ‘environment of care’. As Till writes, ‘urban space must be understood as inhabited worlds infused with many forms of value, rather than as property or according to capitalist forms of exchange-value only’. In what ways will this new place be valuable? How will it support the networks and communities around it? How will it acknowledge their contributions to the neighbourhood? How will it create feelings of belonging? How will it sustain plant, animal and insect life?

5 – If your plans involve creating open space that is intended for public use, consider deeply the inclusivity of your designs. Is it easily read as public, not private? Is it barrier-free? Does it look inviting? As Susannah Hagan writes, ‘the highest level of inclusion possible should be aimed for, because the social and physical health of a city is measured… by the condition and use of its public spaces. They are a barometer of the city’s success or failure in promoting a social environment open and stable enough to tolerate, if not embrace, difference.’

6 – Are you creating a genuine space for encounter – those ‘fleeting encounters that comprise city life’ (Vertovec 2007)? Can you predict who exactly will use this space, or are you uncertain? How does that uncertainty make you feel – do you see it as something to be encouraged, or as a negative? Why?

7 – And finally, if you’re not working with that community group, then why not? They live in the area: they’re the experts. Don’t miss out on knowing what they know: give them the opportunity to fill the place you make with value and meaning.

When you’ve asked yourself all these questions and had another look at your brief, remember: keep asking questions along the way.

The more you ask of yourself and others, the more likely it is that you will create a place to which people become genuinely attached; a place which they will need, want and use for years to come.

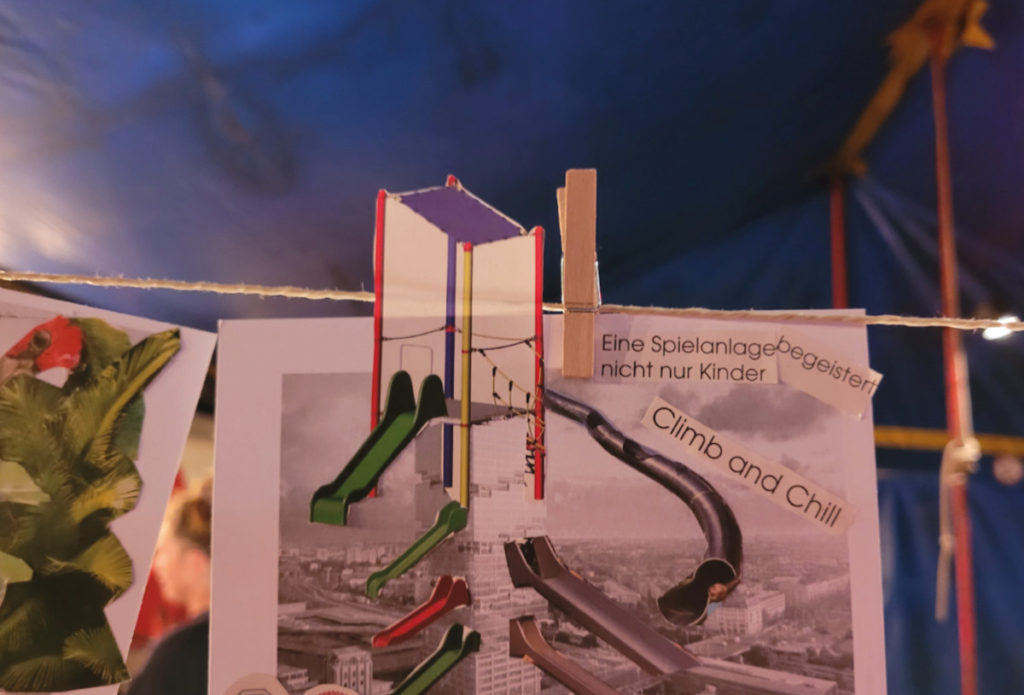

This letter was informed by the research undertaken for my thesis – ‘The Kiez is not asleep: Conflicts between Placemakers, Placekeepers and Displacers in the Markgrafendamm Neighbourhood, Berlin’. And particularly by the focus groups I conducted with residents to generate ideas about how urban development could be made genuinely participatory and community-centred.

References:

Cresswell, T. (2015): Place: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York.

Hagan, S. (2019): Designing London’s Public Spaces: Post-War and Now. Lund Humphries: London.

Huber, D. (2015): ‘Beyond Belief: the Architecture of Lacaton and Vassal’. Art Forum Vol. 53, No.9.

www.artforum.com/features/beyond-belief-the-architecture-of-lacaton-vassal-223877/

Till, K. (2012): ‘Wounded Cities: Memory-work and a place-based ethics of care’. Political Geography Vol. 31, pp.3-14.

Tuan, Y. (1977): Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press: Minnesota.

Vertovec, S. (2007): ‘New Complexities Of Cohesion In Britain: Super-Diversity, Transnationalism And Civil-Integration’ for the Commission on Integration and Cohesion. Queen’s Printer and Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office: London. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/sites/default/files/2009-01/docl_7004_982963564.pdf [Accessed: May 20 2023].

Credit photos Olivia Hanson unless stated otherwise.