Written by:

Last year, I helped my mother move into a new home. As a fiercely independent woman in her eighties, my mother was keen to maintain a small flat of her own, but she now needed more help than we her children (working full time and living at some distance from her) could offer. She knew she was entering a new phase of life and that where she had been living was no longer suitable. We discussed her moving in with us, but she was not keen, having lived alone for many years and preferring her own space. Her disabilities also made our house impractical for her and, with the best will in the world, cohabitation would have required us to move homes to accommodate her safely and comfortably. She was adamant that she did not want this.

We were fortunate to find an extra care environment which would allow my mother to maintain an independent flat, but with a menu of support from in-house staff, including trained carers. We were delighted that my mother qualified for this building, and with the support of her council and the housing association that manages the building and their on-site care team (and a bit of logistical help and physical labour from her family) she and her service dog moved into their new home just before Christmas.

The combination of an independent flat within a building equipped with a flexible in-house care team was a game changer for us. It meant that my mother would have help with some of the everyday tasks that were becoming more difficult for her, and that she would have someone available 24/7 in the case of an emergency. She could rely on a clear timetable of visits from a team of carers who she got to know, and who got to know her. This was a welcome change from her previous situation, in which carers travelled great distances between those they were supporting, often arriving late, flustered and exhausted. The housing association has an agreement with a local GP surgery to provide regular visits to the building, visiting several residents with each visit, and helping to ensure medications are prescribed, delivered and dispatched to residents. The building also offers a lunch service, to ensure that all residents have access to at least one hot meal cooked for them every day.

What we didn’t expect was that this move would make my mother more independent in many ways than she was before. The flat, which was designed specifically to cater for those with disabilities, meant that she was able to move about her home with greater freedom, and to be more active. A kitchen that was better suited to her needs meant that she started to enjoy cooking for herself again, something she had found increasingly more difficult and less enticing in her previous home.

Now living in a much denser urban environment, she found she could walk to the local supermarket, just minutes from her building, with her mobility aid. In her previous home, the trip to the supermarket involved getting her and her mobility aid into her car three times, which just felt too exhausting, and she had come to rely on home delivery services from the supermarket. She had missed looking at and choosing the food she ate and found that she had thrown quite a lot of food away because of food being delivered so close to its sell-by date.

While my mother had been reluctant to give up her car, she quickly decided that it was more trouble than it was worth in her new urban context. She has found that she has most of what she needs on her doorstep, including two cinemas, art galleries, shops and restaurants and a large pedestrianised area with multiple pocket park spaces, which are well maintained and where she can watch the seasons change through their thoughtful planting. There is a university as well as a primary school nearby, and she enjoys seeing children arriving at school in the morning and hearing them playing in the playground at lunchtime. She has come to know a community of fellow dog walkers, and people who work in the restaurants and the various buildings she passes daily on her walks. Whilst she lives in a building designed to care for people with significant care needs, she is managing to lead an active, independent life.

She is extremely happy in her new home, and for my family, her being there has brought us a huge sense of serenity. We can pop in and see here regularly, and with a bit of help from us, my mother feels happy and able to host family gatherings in her own home, something she absolutely treasures.

I am sharing this rather personal story because it highlights so much about what is important about designing for dignity and independence, both for older and disabled people. We know that we were extremely fortunate to find this home and environment for my mother, and that her council was able to help her make the move there and to contribute to her care. We are fortunate that this building is located in an urban environment that is well designed and cared for, and I think is one of the few examples of a large-scale development really producing a high-quality mixed use urban environment. However, I put it to you that there are some important lessons we can draw from my mother’s experience that should apply everywhere:

- We need to start thinking more systematically about housing provision, acknowledging and catering for the different stages of life and for the diverse needs of different people. Housing provision cannot just be about getting x number of homes built. We need a complex system of different housing types for different needs, and to make these accessible to people regardless of their financial circumstances.

- We cannot look at housing provision in isolation. Within our urban environments, homes fit into a complex system of amenities and services, and the connectivity between the two has a huge impact on our quality of life. Easy access to a range of amenities and green spaces on foot can improve our health and wellbeing and our quality of life, stimulate our senses and enrich our personal interactions. It can also reduce our reliance on cars and help us dedicate more resources to maintaining a balance between natural and built elements within our neighbourhoods.

- Housing, health and social care should be better connected. Our homes play a huge role in our health and wellbeing, but the provision of shelter is not enough. How can we ensure that those who are most vulnerable can plug into a system of care and support that offers what they need, but that also benefits from the efficiency and economy of connected services? How can those same principles also be applied to the rest of us? Surely some of these efficiencies could benefit us all.

There is so much we can do to improve the way we are building homes and shaping neighbourhoods in this country. If you have some ideas to share, please join our upcoming Glass-House Chat Can housing be a catalyst for great places? Online on Thursday 17 October.

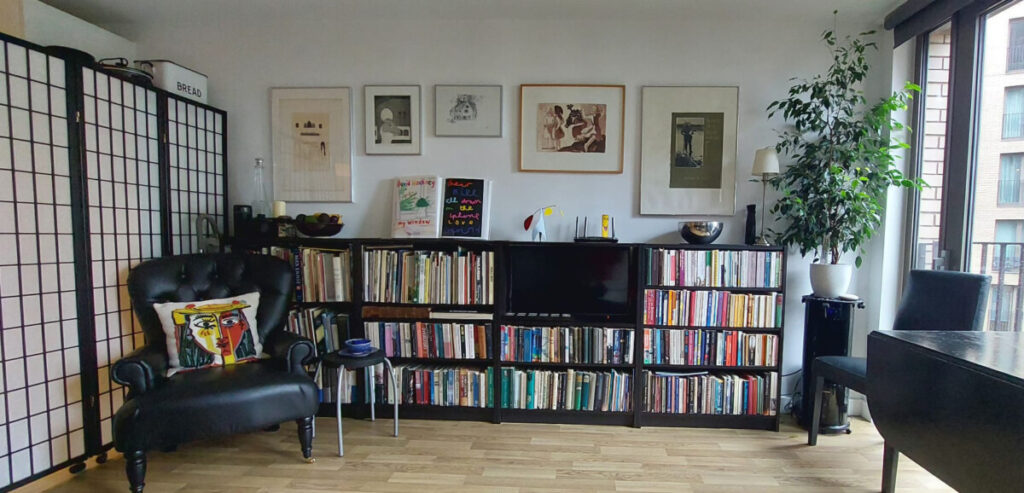

With thanks to my wonderful and inspiring mum for letting me share her story and an image of the beautiful home she has created.